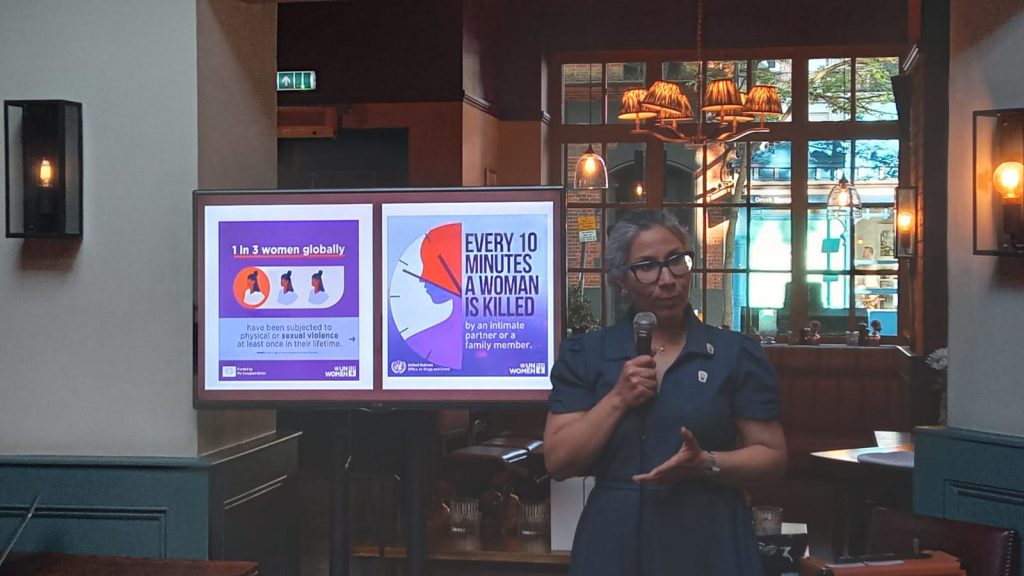

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a global violation of human rights that damages health and wellbeing across the life course and across generations. Except in its most obvious manifestations as acute injury or distress, VAWG has been largely hidden from the awareness of health services.

At a UK national policy level, this started to change with mandatory reporting policies on female genital mutilation, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) safeguarding standards and toolkit, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) domestic abuse guidelines. However, evidence-based guidance is not yet systematically implemented in clinical education and practice.

National and local VAWG prevention policies are siloed, despite the overlap of different types of VAWG, often affecting the same families, and often part of intersectional vulnerability, amplifying other sources of inequality: class, deprivation, ethnicity, gender identity, disability, and poor mental health.

VISION Director and Professor of primary care at the University of Bristol, Gene Feder, and his Bristol colleagues, argue that the role of general practice needs to be based on the evidence for effective interventions. Despite the relatively recent recognition that violence prevention and mitigation is part of health care, that evidence has grown rapidly over the past two decades. It is strongest for the training of primary care teams linked to a referral pathway to the specialist domestic abuse sector in the UK as well as post-disclosure specialist support for survivors.

Experience of domestic violence and abuse is difficult to disclose and may endanger the patient if the abuser learns of disclosure. Disclosure may be even less likely with the increase of remote and digital access to general practice. Therefore, training for all clinicians should include how to ask about abuse, including in online or telephone consultations, how to appropriately and safely respond to disclosure, and to safely document in the medical record.

Although associated with inequality, VAWG is present in all communities. Prevention and mitigation needs to be across all sectors, with investment in interventions with individuals, families, communities, and tackling structural drivers of violence. General practice must be part of this societal response.

Key messages

- There is overlap between different types of violence often affecting the same children, families, and households.

- Intersections of deprivation, disability, poor mental health, and racism amplifies the effect of violence and trauma, also reducing access to general practice support.

- Violence against women and girls (VAWG) requires a team-based general practice response underpinned by trauma-informed training and referral pathways to specialist services, often in the voluntary sector.

- Effective responses to VAWG needs to be rooted in trauma-informed care, facilitated by relational continuity and enabled by face-to-face consultations.

- Clinician experience of violence and abuse needs to be addressed in training and support.

To download: Violence against women and girls: how can general practice respond?

To cite: Violence against women and girls: how can general practice respond? Gene Feder, Helen Cramer, Lucy Potter, Jessica Roy and Eszter Szilassy. British Journal of General Practice 2025; 75 (756): 297-299. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2025.0244

For further information, please contact Gene at gene.feder@bristol.ac.uk

Photograph licensed under Adobe Stock subscription