On Thursday 19th October 2023, Dr Elizabeth Cook was invited to contribute to an event organised by Public Policy Exchange on Combatting Knife Crime in the UK. With contributions from Professor Lawrence Sherman, Professor Kevin Browne, Bruce Houlder CB KC DL, Nathaniel Levy, Dr Sue Roberts, and Sammy Odoi, the event examined current government strategy and policy responses to knife crime. Applying Carol Bacchi’s (1999; 2009) ‘What’s the problem represented to be?’ (WPR) approach, Elizabeth made the case for a gender analysis of ‘knife crime’, a summary of which is provided below.

What’s the problem represented?

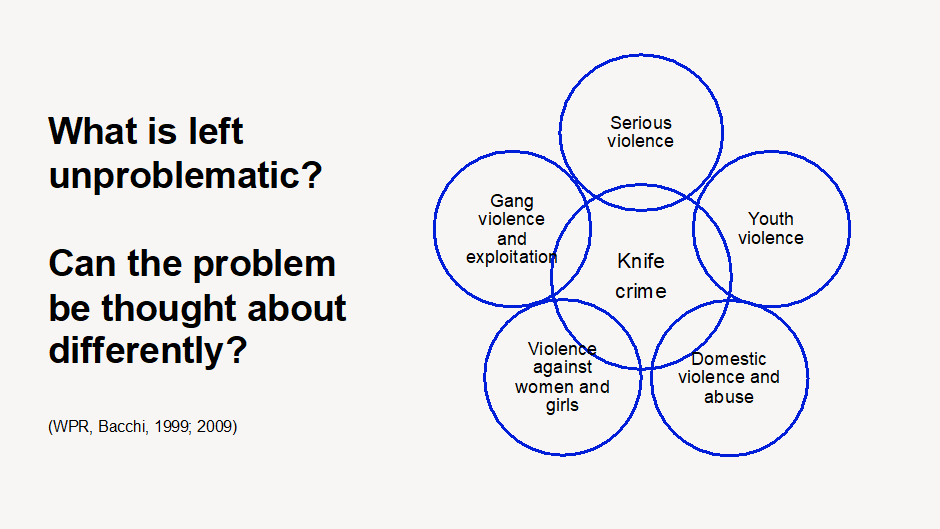

Knife crime is a policy priority that ranks consistently high on the government agenda, appearing in key strategic areas such as serious violence, ‘gang’ involvement and exploitation, and children, young people, and vulnerability. Cutting across these strategic areas is a particular attention to tackling county lines and the misuse of drugs, restrictions on weapon-carrying and possession, early intervention and prevention programmes with young people, and community partnership responses and safeguarding.

What are the assumptions underpinning these representations?

There are key assumptions that underpin these representations of knife crime in public policy, each linked to specific ideas about:

- who exactly is at risk,

- where is considered to be safe,

- who is vulnerable to harm,

- and, on the whole, what forms of violence are deemed to be ‘serious’.

Constructions of knife crime as they currently stand, depict the problem as one committed primarily by and against men, occurring in public spaces, often between young people, and as an issue that is increasingly racialised in media and public discourse. The evidence base for each is not to be ignored and there are key takeaways from each policy approach which contribute one piece of a puzzle.

However, taking a WPR approach, there are questions to be asked: What is left unproblematic and what harms and whose voices are missed as a result?

There are key elements that are omitted from current policy approaches to knife crime and lessons to be learned from the violence against women and girls sector which have been relatively absent so far.

What is left unproblematic? Can the problem be thought about differently?

Various sources of evidence highlight that knives are consistently the most frequent method of killing in the context of intimate partner homicide by men against women. While the proportions fluctuate (e.g., ONS 2023; Femicide Census, 2020; VKPP, 2023), it stands that when women are killed by men, they are most likely killed using a knife.

What effects are produced by this problem representation?

Considering that up to 1 in 3 victims of homicides using a knife are women, it is problematic that there is so little analysis of sex/gender in policy responses (see, MOPAC 2017, for an exception). This has serious implications for how interventions are identified.

For example, efforts to regulate offensive weapons through legislation hit a wall when it comes to domestic abuse committed within the home. There have been several proposals over the years to either blunt kitchen knives or confiscate particular knives in the possession of known domestic abuse perpetrators – the assumption here being that the removal of the weapon is the removal of risk. However, the fundamental issue in domestic abuse is that anything is a weapon.

These raise questions about what (or who) is considered to be a source of risk and what can be done to reduce it.

How can we disrupt the problem representation?

While public health approaches to violence frequently invoke the need for multi-agency and partnership working, this must also translate to policy and implementation in strategy as well as practice. This means further work to avoid and break down policy siloes and assumptions in problem representations.

See the article, free to access, here:

Cook, E. A., & Walklate, S. (2022). Gendered objects and gendered spaces: The invisibilities of ‘knife’ crime. Current Sociology, 70(1), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120932972

References

Bacchi, C. (1999) Women, Policy and Politics: The construction of policy problems, London: Sage.

Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be? Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia

Bates, L., Hoeger, K., Nguyen Phan, T.T., Perry, P. and Whitaker, A. (2022) Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme (VKPP) Domestic Homicides and Suspected Victim Suicides 2021-2022: Year 2 Report. Available at: https://www.vkpp.org.uk/assets/Files/Domestic-Homicide-Project-Year-2-Report-December-2022.pdf

HM Government (2018) Serious Violence Strategy. London: HM Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5acb21d140f0b64fed0afd55/serious-violence-strategy.pdf

Long, J., Wertans, E., Harper, K., Brennan, D., Harvey, H., Allen, R. and Elliott, K. (2020) UK Femicides 2009-2018. London: Femicide Census. Available at: https://www.femicidecensus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Femicide-Census-10-year-report.pdf

MOPAC (2017) The London Knife Crime Strategy. London: Greater London Authority. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/mopac_knife_crime_strategy_june_2017.pdf

ONS (2023) Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2022. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/homicideinenglandandwales/march2022/pdf

For further information, please contact Lizzie at elizabeth.cook@city.ac.uk