Workplace violence is a significant problem with underexamined productivity effects. In a global survey, just under 1 in 5 workers reported exposure to psychological violence and harassment at work, and 1 in 10 reported exposure to physical violence during their working-lives. In the United Kingdom (UK), the Health and Safety Executive (the regulator for workplace health and safety) found 1% of all adults of working age, in the 12 months prior, experienced a physical assault or threat of assault at work.

Workplace violence covers a broad range of adverse social interactions and behaviours committed by or towards employees. It includes encounters between colleagues and between workers and service users. It can also include incidents of domestic abuse experienced at work, with abusers known to pursue victims in the workplace.

Direct and indirect exposure to violent acts or threats of violence at work can be anticipated to lead to anxiety and fear of further victimization. Workplace violence, especially when persistent, may cause psychological disorders including common mental disorders (CMD) of generalized anxiety and depression.

VISION researchers Dr Vanessa Gash (City St George’s University of London) and Dr Niels Blom (University of Manchester) used the United Kingdom Household Panel Study, a nationally representative survey with mental health indicators to examine the prevalence of violence and fear of violence by sector and the effect of violence on common mental disorders (CMD) risk. They also supplemented the analyses with the views of those with lived experience.

Their study, Workplace violence and fear of violence: an assessment of prevalence across industrial sectors and its mental health effects, examined variance in the prevalence of workplace violence and fear of violence in the UK by industrial sector and determined the mental health effects thereof using longitudinal data.

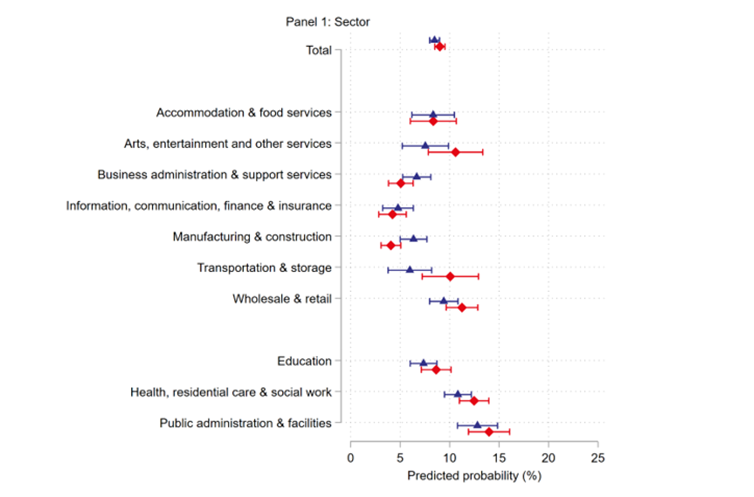

Results showed that a high prevalence of workplace violence and fear of workplace violence was found in multiple different UK industrial sectors – >1 in 10 workers were exposed to violence in the last 12 months in 30% of sectors and >1 in 20 workers were exposed in 70% of sectors. Workers employed in public administration and facilities had the highest risks of workplace violence. The second highest sector was health, residential care, and social work. Workplace violence increased CMD risk as did fear of violence at work. Also, the effect of violence and fear of violence on CMD remained when the researchers investigated CMD one year later.

Recommendation

The researchers recommend better recognition of the extent to which workplace violence is experienced across multiple sectors and call for better systems wide interventions to mitigate the associated harms.

To download: Workplace violence and fear of violence: an assessment of prevalence across industrial sectors and its mental health effects

To cite: Gash, V, Blom, N. ‘Workplace violence and fear of violence: an assessment of prevalence across industrial sectors and its mental health effects’. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4230

For further information, please contact Vanessa at vanessa.gash.1@citystgeorges.ac.uk

Illustrations from Geisa D’Avo and copyright owned by UKPRP VISION research consortium