Can the ONS new combined measure of violence be used to accurately assess progress in reducing violence against women and girls?

Blog by Dr Polina Obolenskaya, Merili Pullerits and Dr Niels Blom

The UK government is expected to publish its new Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) strategy later this year. The strategy is part of a broader ambitious commitment to halve VAWG within a decade. A new combined measure of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and stalking, developed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), has been proposed to serve as the main benchmark for evaluating progress toward this commitment.

Here we outline three main concerns the VISION consortium has with the proposed approach.

Lack of historical continuity

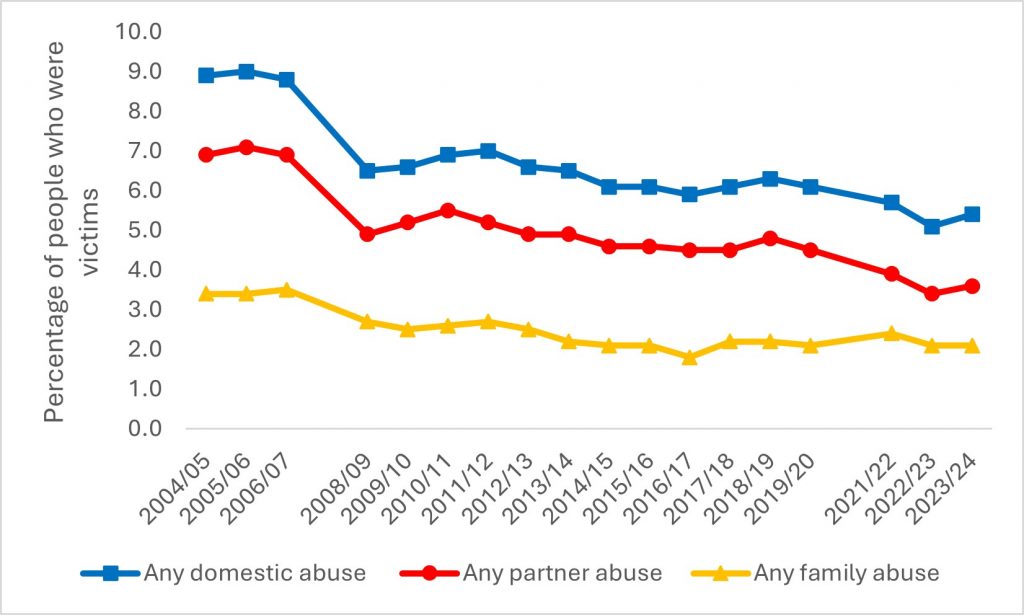

To assess the effectiveness of the VAWG strategy, historical continuity is crucial. Rates of domestic abuse in England and Wales have declined in recent years (Figure 1). Therefore, any assessment of a decline or rise in VAWG needs to be placed in the context of broader declining violence rates. Without this historical continuity, the government cannot distinguish between improvements driven by their strategy and those resulting from long-term social changes that were already underway.

Figure 1 Prevalence of domestic abuse in the last year among people aged 16 to 59 in England and Wales, 2004/05 to 2023/24

Source: Office for National Statistics 2025, Figure 3

However, the new combined measure disrupts this continuity. This is due to changes to the question wording and structure of its composite measures. The new combined measure of VAWG consists of self-completion data from a newly developed Domestic Abuse module (piloted in 2022/23 and 2024/25, and fully implemented from 2025/26), as well as a combination of the old and new Sexual Victimisation module (piloted in 2025/26 and planned for full implementation from 2026/27).

The new Domestic Abuse module had undergone a complete redevelopment, with extensive negative repercussions for historical continuity, which we have outlined previously. While the sexual victimisation module is not being re-developed as considerably, the comparability of the new data to the previously collected data can only be assessed once the first round of results is available. This means a new stable and comparable measure will not be available in its final form until the 2026/27 data collection, despite the government’s strategy period beginning in 2025/26.

Without historical continuity, it will not be possible to produce long-term trends over time in the composite measure of VAWG for England and Wales for some years to come. Given the decline of some forms of violence in recent decades, it is important to examine whether any decline in VAWG is due to genuine policy success, or due to a continuation of pre-existing trends.

Incomplete scope of violence

While the government has indicated that it intends to supplement the new combined measure of domestic abuse, sexual victimisation and stalking with additional metrics, it is currently unclear what these supplementary measures will include or how they will be weighed against the main benchmark. In any case, the narrow scope of the new combined measure has been raised as a concern both among academics and others working in the sector.

Some of the limitations of the measure are due to the unavailability of certain measures in data it is based on – the Crime Survey for England and Wales. The End Violence Against Women coalition (EVAW) has highlighted that the new measure fails to reflect the full spectrum of violence experienced by women and girls, omitting online abuse, child abuse, ‘honour’-based abuse and sexual harassment (EVAW blog) as well as Female Genital Mutilation (EVAW briefing). These exclusions, as EVAW argues, risk distorting the true scale and impact of VAWG. Additionally, given alarming rates of teenage relationship abuse (e.g. Barter et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2013), we consider its exclusion to be a serious oversight in measuring VAWG – including girls – effectively. Since the combined measure excludes experiences of girls under the age of 16, its use as a main tool to measure government’s ambition to half ‘Violence against women and girls‘ may be misleading.

While the gaps outlined above stem from the limitations of the Crime Survey for England and Wales, we also have concerns about the scope of the measure which could be addressed with the data already available.

Firstly, the new combined measure excludes other offences which count within the CSEW as ‘violent crime’ or violence against a person. While men are more likely to be victims of such offences, disregarding women’s experiences of these risks undercounting their overall risks and impacts of violence (Cooper & Obolenskaya, 2021; Davies et al., 2025). For example, while a substantial amount of VAWG is covered by domestic abuse, sexual violence, and stalking, women also experience violence in other aspects of life, such as at work or in public spaces. Accounting for the above offences significantly increases the proportion of people experiencing violence and more accurately reflects the extent of violence experienced by women and girls.

Secondly, the new combined measure omits broader violence-related offences, for which data are available in the CSEW. This includes threats of violence and other criminal offences which are coded as ‘non-violent’ by the ONS (due to a methodological process involving priority ordering of offences), even though they involve the threat or use of force or violence (Davies et al., 2025; Pullerits & Phoenix, 2024). These offences should be included in any overall measure of VAWG regardless of who is most affected. However, their omission is especially problematic given that they disproportionately affect women (Davies et al., 2025; Pullerits & Phoenix, 2024), meaning the headline measure is likely to underestimate women’s experiences even further.

Although the government has suggested that other metrics are planned to be used, separately, to assess progress towards halving VAWG, having a narrow main measure risks reinforcing outdated gender norms where women are considered to be more affected by what happens at home rather than outside of it. Such a perspective fails to capture emerging forms of abuse and fails to reflect the full spectrum of women’s lived experiences with violence.

Technical and transparency concerns

We have previously raised concerns about the new Domestic Abuse module, and are further concerned about the ways it is integrated into the new VAWG combined measure:

- Collected new Domestic Abuse data had not undergone statistical validity and reliability checks and had not been subjected to wider scrutiny (as raised by VISION previously) before the decision to replace the old module with it was finalised.

- Changes to the Domestic Abuse and Sexual Victimisation modules appear to have been made independently from each other, with limited coordination across the survey modules. Given the similarity in the phrasing of a few questions across the modules, this lack of foresight and integration appears to have resulted in overlapping content that could lead to confusion both for respondents and for those interpreting the data.

- The development process has lacked transparency and consultation with external stakeholders, as raised by EVAW.

Recommendations for improvement

The ONS’s new combined measure of VAWG risks oversimplifying the complex realities of violence against women and girls. Even with supplementary metrics, relying on such a narrow primary benchmark – which lacks historical continuity and is limited in scope – will not adequately support evidence-based policy development or serve the needs of those most affected by violence and abuse.

To ensure more meaningful monitoring, we have three key recommendations to the ONS:

Prioritise historical continuity in Domestic Abuse data collection: We urge the ONS to revert to a Domestic Abuse module that aligns more closely with the previous version to ensure data continuity. While we welcome the inclusion of new questions on coercive control and family-related violence, we strongly believe these additions could be integrated into the long-standing existing framework without disrupting the historical comparability of the data. If a full reversion is not feasible, we recommend that theONS takes steps to ensure meaningful assessment of change and continuity using the new measure. These steps should involve: publishing clear comparability assessments between old and new measures; providing bridging data where methodologically possible; and maintaining transparency about limitations.

Broaden the scope of the ‘combined’ measure and make it explicit that it does not fully reflect the experience of girls: the definition of violence against women and girls should be expanded by using existing CSEW data to include “violence against the person” offences, as well as, possibly, other incidents where violence or threat of violence took place but that are not coded as “violent crime” by ONS. The CSEW currently provides insufficient coverage of technology-facilitated and online abuse, which should be a development priority going forward, given the increasing prevalence of these forms of violence both within domestic contexts but also outside of them. Additionally, since the combined measure does not capture violence experienced by girls under the age of 16, the government needs to make it clear that the headline measure, should it be used in the strategy, reflects only experiences of (young) women, not girls.

Enhance transparency and accountability in survey development: we call on the ONS to address technical and transparency concerns regarding their measures and commit to greater openness in their approach. Any new module should be subject to timely, transparent analysis and external scrutiny of it before it becomes a permanent change in the survey.

If the government is genuinely committed to halving violence against women and girls within a decade, it must first ensure its measurement approach is comprehensive, meaningful and methodologically sound. Relying overwhelmingly on a narrow headline measure risks presenting an incomplete picture of the problem of VAWG, and risks undermining both accountability and progress.

For further information, please contact Polina at polina.obolenskaya@citystgeorges.ac.uk

References

Barter, C., McCarry, M., Berridge, D., & Evans, K. (2009). Partner exploitation and violence in teenage intimate relationships. Online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265245739_Partner_Exploitation_and_Violence_in_Teenage_Intimate_Relationships

Cooper, K. & Obolenskaya, P. (2021). Hidden Victims: The Gendered Data Gap of Violent Crime, The British Journal of Criminology, 61(4): 905–925. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa100

Davies, E., Obolenskaya, P., Francis, B., Blom, B., Phoenix, J., Pullerits, M. & Walby, S. (2025). Definition and Measurement of Violence in the Crime Survey for England and Wales: Implications for the Amount and Gendering of Violence, The British Journal of Criminology, 65(2): 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azae050

End Violence Against Women Coalition (EVAW) (2025). New ONS crime data fails to capture full spectrum of VAWG. Blog, July 2025, online: https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/new-ons-crime-data-fails-to-capture-full-spectrum-of-vawg/

End Violence Against Women Coalition (EVAW) (2025). A mission to halve Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG): A VAWG sector briefing on metrics and their limitations. Briefing, June 2025, online: https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/VAWG-Metrics-Doc.pdf

Fox, C. L., Corr, M. L., Gadd, D., & Butler, I. (2013). Young teenagers’ experiences of domestic abuse, Journal of Youth Studies, 17(4), 510–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.780125

National Audit Office. (2025). Tackling violence against women and girls (HC 547). Online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls.pdf

Office for National Statistics (2025). Developing a combined measure of domestic abuse, sexual assault and stalking, England and Wales: July 2025. Article, online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/developingacombinedmeasureofdomesticabusesexualassaultandstalkingenglandandwales/july2025

Office for National Statistics. (2024). Domestic abuse prevalence and trends, England and Wales: Year ending March 2024. Article, online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseprevalenceandtrendsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024

Pullerits, M. & Phoenix, J. (2024). How Priority Ordering of Offence Codes Undercounts Gendered Violence: An Analysis of the Crime Survey for England and Wales, The British Journal of Criminology, 64(2): 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azad047

VISION (2025), Implications of changing domestic abuse measurement on the Crime Survey for England & Wales. Comment, online: Implications of changing domestic abuse measurement on the Crime Survey for England & Wales – City Vision