Exploring guiding principles for ‘Doing Co-Analysis Justice’

Blog by Dr Annie Bunce, VISION Research Fellow

How can researchers meaningfully and ethically involve people with lived experience of the criminal justice system in data analysis?

This is the question myself, a group of VISION colleagues (Lizzie Cook, Polina Obolenskaya, Sian Oram, Les Humphreys and Sally McManus), Dani Darley (University of Sheffield) and a group of Revolving Doors’ (Home – Revolving Doors) lived experience members, explored via a face-to-face workshop in May and online feedback session in July, funded by City’s Participatory Research Fund.

Co-production, lived experience engagement, participatory research and patient and public involvement (PPI), amongst others, are increasingly common terms in academia and the wider research landscape. Guidelines and toolkits are popping up for doing participatory research with, for example, children and young people (Participation toolkit | Children and families affected by domestic abuse); survivors of domestic abuse (Review Resources on Survivor Involvement – VAMHN); children and young people in conflict with the law (Golden-Rules-young-people.pdf), and involving those with lived experience in criminal justice reform (PRI_10-point-plan_Lived-experience.pdf).

These broad principles on doing participatory research are useful and have guided my approach to multiple recent projects. But something I noticed is that there is generally less guidance on involving people from marginalised groups, particularly those with lived experience of the criminal justice system, in the data analysis stage of research projects specifically. Despite the analysis being at the heart of the research process. Essentially, activating the “co” in co-analysis is still somewhat of a mystery. And whilst a definitive “how-to” guide to collaborative data analysis alongside stakeholders would be at odds with the flexibility and relational grounding that are the beauty of co-analysis, a little guidance could make the process smoother and more enjoyable for everybody involved. Without this, quite a lot of angst can be caused repeatedly asking yourselves: Are we trying to do too much? Are we doing enough? How much can we afford to do? How much do people actually want to be involved? How can we make this happen?

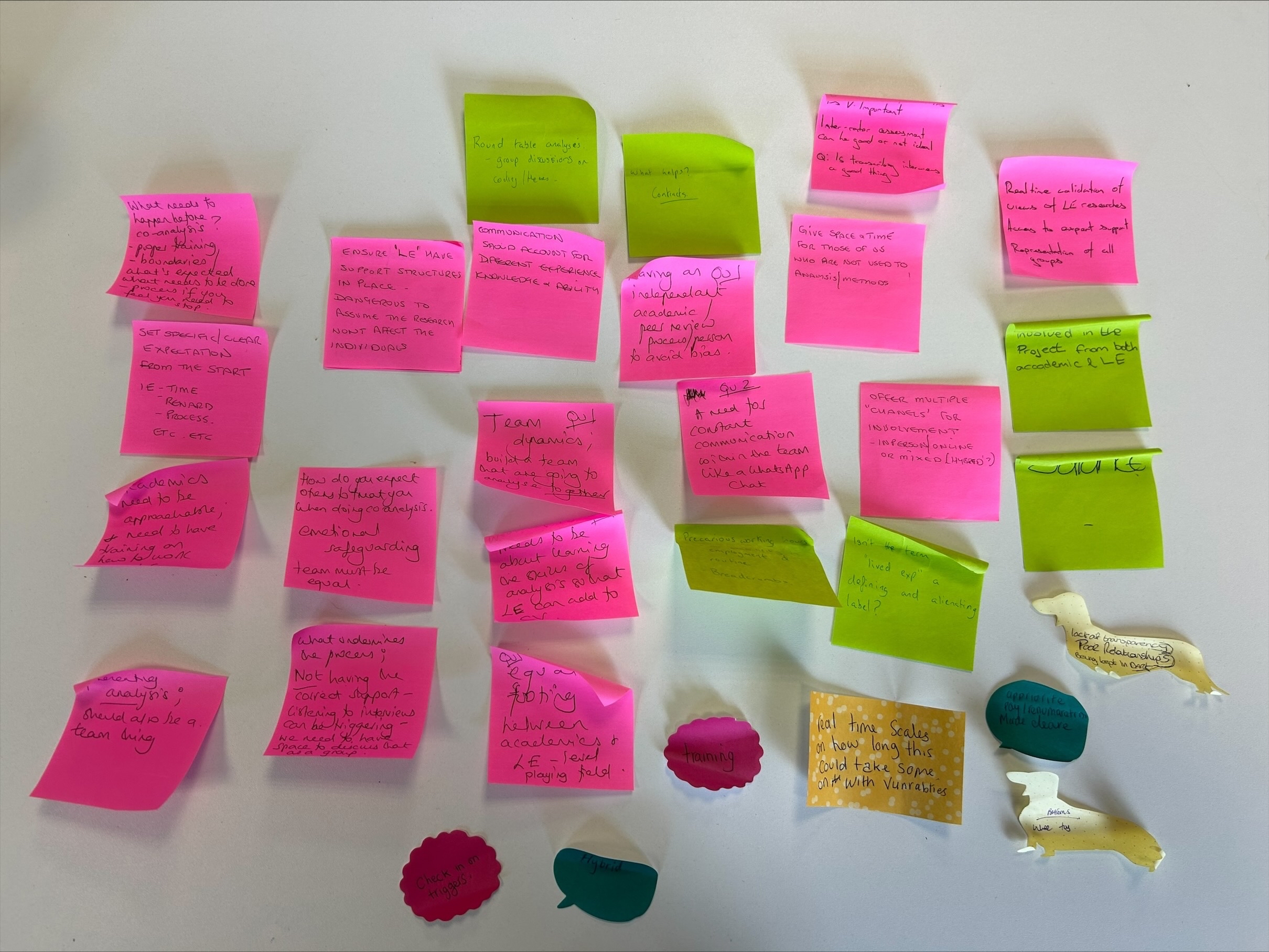

Ironically, a fair bit of time in our workshop to co-produce some best practice principles for doing co-analysis was spent going round in circles tackling questions around how to do it. Ultimately, the best approach to co-analysis depends on various factors, including the type of data being analysed, people’s individual experiences and preferences and access to resources etc. Nevertheless, addressing these questions openly and collaboratively, welcoming and respecting everybody’s perspective and actively thinking about all the factors that need to be considered, made for an enlightening and productive discussion. From which themes have been identified and are currently being transformed into principles (watch this space).

A few spoilers:

- Lots of ‘p’ words are involved, including planning, preferences, perfection, practicality and power

- Transparency and avoiding tokenism are two of the most important principles for our participants in determining whether they found co-analysis enjoyable or not

- Ethical standards and institutional processes need reframing if they are to authentically support participatory projects involving co-analysis

- Co-analysis is messy, heavy and can’t just be squeezed in as an extra; the emotional labour that goes into both managing and participating in co-analysis must be valued

- Co-analysis can also be fun. People with lived experience want to have fun with it, and it’s nice for them when academics can even have a bit of fun as well

For further information, please contact Annie at annie.bunce@citystgeorges.ac.uk

Photographs:

- Top: Post-its from the VISION – Revolving Doors co-analysis workshop

- Bottom: Annie Bunce, VISION Research Fellow